Article by Ulrich von Bülow about the Heidegger Nachlass.

We get some interesting information in this article:

Heidegger’s Nachlass was organized and put in a certain order by Heidegger himself and by Walter Biemel in 1973.

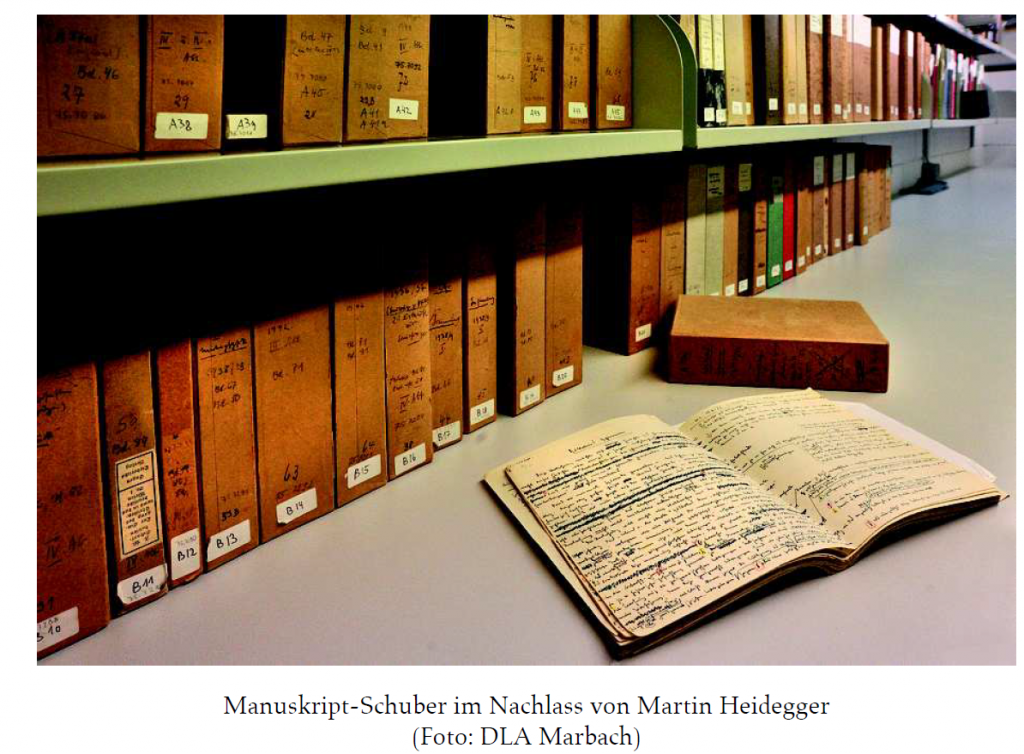

There are in total 173 boxed sets which are divided in A, B, C, and D.

The B-,C-, and D-sets entail texts of diverse kinds: lectures, speeches, preparational works, notes.

It looks like this in the Archives in Marbach (I don’t think they keep these sets still on the bare ground).

Von Bülow claims that Heidegger consciously delibaretely chose which manuscripts to keep (and which should be destroyed). (but he does not elaborate why he thinks that)

Von Bülow then ( 307ff.) discusses whether Heidegger preferred writing or talking (about philosophy). All in all, what von Bülow lists here is not very convincing. But that is not von Bülow’s fault. Rather, it is Heidegger who presents this matter in different versions. Sometimes he seems to prefer the written word, sometimes he seems to favor the fluidity of discussions. Von Bülow is quoting Heidegger here where he argues that the written word is superior; but I could give even more quotations where Heidegger attributes that superiority to the spoken word.

As we could have imagined, Heidegger was someone who preferred writing everything with his own hands. Not with any machine. Not with the Schreibmaschine. In this context, von Bülow, for the first time, mentions the word “Hand-Werk” from the title of his article. He still understands it quite literally: writing, in this case, is a “Hand-Werk”; typing with a typewriter is not a “Hand-Werk”.

However, von Bülow quotes Heidegger in a footnote, where already more dimensions of this word shine through: “Die Schreibmaschine entreißt die Schrift dem Wesensbereich der Hand, und d.h. des Wortes.” (GA 54, 119). What’s interesting in this quote is that the “Wesensbereich” of the hand is identified with the “Wesensbereich” of the word. Von Bülow is not discussing this quote; but already we see a mysterious different meaning of the concept “Hand-Werk” coming forth. How is it that Heidegger can identify the Wesensbereich of the hand with that of the word? What has the “word” to do with the “hand”?

(Heidegger’s Handwriting, The title reads: Der Weg zur Sprache. After that: “Am Beginn dieses Vortrages stehe ein Wort von Novalis. Es findet sich in einem Text, den er überschrieben hat: Monolog. Der Titel deutet in das Geheimnis der Sprache, daß sie …) (The Published version reads: “Zum Beginn horen wir ein Wort von Navalis. Es steht in einem Text, den er Monolog überschrieben hat. Der Titel deutet in das Geheimnis der Sprache: …” (see: GA 12, 227).)

Von Bülow continues without dwelling on the mystery of the “Hand-Werk”. He says a few things about how meticulous Heidegger prepared his public lectures and speeches. And that Heidegger even used different colours in his manuscripts to indicate pauses and emphases. Rhythm and Melos of the spoken word are essential, and perhaps not that present in the written word. … Not very surprising stuff, so far.

A problem I have with von Bülow’s article appears on p. 310. After quoting Heidegger about how important the seminars were (which would apparently be a contradiction to what von Bülow said in the beginning about Heidegger preferring the written word), von Bülow gives a rather strange interpretation of Heidegger’s words. To be fair, Heidegger is not providing any reasons as for why he thinks the seminars are so important. But Von Bülow interprets: when talking to each other, one is “forced” to “react instantly”, and what has been said cannot be erased or edited. — After that, von Bülow follows up with a few very broad descriptions that the spoken word in discussions requires “all senses” to be present; and that every conversation (Gespräch) is alive, or at better: livid (ein lebendiges Gespräch).

But has von Bülow captured what is essential about this Gespräch by the two aspects of “I have to react instantly” and “We cannot change what has been said”? What does he mean with “all senses are required”? Hearing – yes; Seeing – yes; Smelling – perhaps yes; tactile senses – well, not really? What about tasting – no? I guess von Bülow is speaking in a non-literal, metaphorical manner that in these conversations everybody must be present with his whole body and mind; to fully engage (oneself) in a talk with somebody, one cannot be distracted. Rather, one must be fully immersed; and in good discussions, one automatically is fully immersed as if one were drawn and pulled into the conversation. In that case, — and many people have written about this phenomenon and more people have witnessed it first-hand — the conversation is “alive” and has a life on its own, so to speak. Time is flying by without being noticed; a feeling of excitement comes over the participants, and so on, and so forth.

Von Bülow is definitely simplifying at this point; and is not fully capturing what “the magic is,” so to speak. He even confines the importance of conversations to the early Heidegger (p. 311ff.); as if only for the early Heidegger conversations were important, not for the late Heidegger. Which is definitely not true. Just see several of the late seminars, the Zollikon or Thor seminars, for instance; wonderful notes now have been published in GA 91, where Heidegger at several points throughout the conversations emphasizes the importance of conversations. A beautiful read, by the way…

And perhaps I am a little bit too nitpicky with this article. Perhaps there could be a more charitable reading of von Bülow’s article, but there is another point that I do not quite agree with. On p. 312f. von Bülow goes on to quote Heidegger a few times from his early Aristotle and Plato lectures, where he talks about how the soul speaks with itself; interpretations of the nous as a dialegesthai, or simply the self-referential structure of the soul – are mentioned in this context. Von Bülow makes the observation that writing and reading are interestingly intertwined; and then concludes: “In this sense, Heidegger’s notes could be understood as communication-with-oneself (Selbstkommunikation)”.

First of all, what’s good in these passages is that von Bülow emphasizes the importance of the (conscious) repetition of what one has read or written (for instance, by translating a text (Heidegger seldomly relied on translations done by others)). This repetition (Wiederholung) is immensely important for Heidegger, for the early and late Heidegger.

But why choose this word “Sebstkommunikation”? First of all, why “Kommunikation”? Which is such a modern word (Habermasian?), from an area that is totally foreign to philosophy, to the humanities, to thinking. But in this combination “self+communication”, it sounds as if Heidegger is talking mainly to himself. Monologues. — Is von Bülow suggesting that Heidegger is only or mainly talking to himself? He wouldn’t be the only one suggesting that, to be sure. But let’s come back to this later.

Again, von Bülow indicates that the written word can be edited (the spoken word cannot). Heidegger even reserved the right side of each and every page for these comments. Heidegger was a slow reader, taking his time with texts, reading them again and again; commenting on them, reading through his comments, commenting on his comments, and so on. Von Bülow calls this a “denkerisches Selbstgespräch” (313), again evoking the bad connotations of someone “talking to himself” which could instead also be described simply in terms of “thinking about something” which is much less negative and does not carry negative connotations. Von Bülow himself – one page prior – has mentioned that “thinking” since the origins of philosophy has been understood as a form of self-reflection in the medium of language. Why then “Selbstkommunikation”, why “Selbstgespräch”?

What’s interesting to know for us about how Heidegger read books, follows on p. 314, where von Bülow describes that Heidegger always used three colored markers when reading and when going through his notes: red, green, and yellow. Von Bülow’s interpretation of the meaning of these colours is as follows: red = essential passages; green = in need of further explanation; yellow = questionable, worthy of criticism (314). (strange is von Bülow’s remarks on the next page in which he tries to draw links between these three different colours and Heidegger’s own method. For example, von Bülow says that “yellow reminds us of the critical method of the ‘Destruktion'” (314); I do not think that Heidegger ever used this word ‘Destruktion’ for tasks related to the editing of an individual passage (Destruktion rather is used in reference to the whole process of attempting to understand history by bringing hidden layers of meaning to the surface that have been covered up by the tradition, etc. Von Bülow is mentioning this himself but still uses the word Destruktion afterwards to explain the use of the color yellow.)

In the fourth chapter, von Bülow then turns to the distinction between “to publish” or “to conceal,” regarding the manuscripts of Heidegger’s Nachlass.

Von Bülow’s interpretation is that Heidegger’s “Kehre” can be understood – nicht zuletzt – as turning away from the audience (322). Von Bülow says that Heidegger wanted to exclude “the public” from his thinking. How? Heidegger allegedly did not talk about what he was thinking and he concealed what he was writing. (323) As a proof for his interpretation, von Bülow refers to Heidegger’s “Contributions” (GA 65) which Heidegger did not want to be published earlier than 50 years after his death. (323)

Von Bülow then indicates that the relationship between what has been made public and is known and what has been concealed and is unknown is similar to that between concealment and unconcealment or the ontological difference between beings (Seiendes) and Seyn (Beyng). However, von Bülow adds: “in gewisser Weise”, which can be translated as “in a certain way”. Von Bülow does not elaborate or explain.

Then, again, a few notes on Heidegger’s manuscripts follow, which, in my opinion, are the most interesting part of this article. For instance, von Bülow explains that Heidegger used symbols and small sketches for his notes. On many other notes, one can find what we would now call “mindmaps” – where Heidegger arranged certain concepts: “Raum” is in the center, arrows are showing different layers of understanding; perhaps “constellations” of concepts, that help to understand what “Raum” is. See the following picture:

Needless to say, I would not agree with von Bülow’s categorization that follows close to the end of the article, which goes like this:

- Before 1927/28: the spoken word is still dominant and preferred by Heidegger

- After 1927: spoken word and written self-criticism – not meant for the public

- After 1945: written word became dominant – not meant for the public

(cf. 326). — This categorization of three phases of Heidegger’s philosophical writing are a broad simplification, of course. Von Bülow would not deny that. But it simplifies to a degree where I do not recognize its value. Perhaps it oversimplifies, or misrepresents. There are too many overlaps. Especially von Bülow’s claim that the spoken word is preferred only be the early Heidegger, is simply wrong. But also the distinction between “meant for publication” and “not meant for publication”, — von Bülow describes the latter as “concealing”, which again, has bad connotations similarly to the use of words such as “Selbstgespräch” and “Selbstkommunikation” — needs much more in-depth analysis.

In conclusion: This article – not to its merit – pursues two different goals: One, to inform the reader about Heidegger’s Nachlass and give information about how Heidegger has arranged the Nachlass, how he has written his notes, and so on. These are biographical notes about Heidegger’s reading and writing habits that are nice to read. But on the other hand, the author, von Bülow, is also trying to provide “philosophical explanations,” and to give his own opinions and interpretations of what is going on, including a rather unconvincing chronological categorization of three phases from “preferring the spoken word” to “writing as a form of thinking or even as a form of talking to himself”. The claim is: The late Heidegger did not write for the public; he also did not talk to the public, but mainly wrote for himself. This writing is either self-criticism as a form of rigorous thinking (von Bülow’s more positive interpretation); or it could be seen as a form of self-communication, which excludes the others. This reading is much more negative, but von Bülow does not explicitly state this; it is only hinted at, it is only suggested that the late Heidegger is increasingly only ever talking to himself.

But just by suggesting this, von Bülow is opening the doors for many misinterpretations of Heidegger’s thinking. This did not happen (yet), but one could imagine that philosophers such as Habermas or Sidonie Kellerer could now quote von Bülow where von Bülow wrote about the “Selbstgespräche” of Heidegger which are not meant to be read by the public; — they could also quote von Bülow where he says that the late Heidegger followed the strategy of “concealment” (verschweigen) regarding his own thoughts– This is not a joke, but Sidonie Kellerer is currently writing a book on exactly this: She claims that Heidegger’s strategy was to conceal his inner and most evil thoughts, employing a indirect and ambiguous writing style that was meant to “fool” his readers. — for this reason, namely because von Bülow does not rule out these misinterpretations by clearly stating that “Selbstgespräch” and “Selbst-Kommunikation” is not meant as a form of isolation, but as a form of rigorous thinking where the thinker tries to approach the subject of his thought (die Sache dieses Denkens),… something that is essential to thinking… for this reason… I do not quite like this article. To be clear: In Heidegger’s “Selbstgespräche”, he is opening up to the world, to other people, to the things that he is currently concerned with; Selbstgespräch does never mean “isolation” or “exclusion” and has nothing to do with other misinterpretations concerning Heidegger’s alleged solipsism.

I must also mention that the title is misleading. Von Bülow is using “Hand-Werk” in the title, but never really explains what Hand-Werk means for Heidegger. Heidegger actually uses that word quite frequently in his late texts. Even in the Black Notebooks, one could find many passages in which Heidegger explains what he means by it. And one thing is clear; he does not only mean “actually using one’s hand when writing notes”; Rather, Heidegger means “much more,” where the “Wesensbereich” of our hands is somehow connected to the “Wesensbereich” of the word. — Explaining what “Hand-Werk” is, requires diving into the complexities of Heidegger’s philosophy of language; but if von Bülow does not aim to do that, why choose this word in the title?

Alright, that it is for today!

All pictures are from the Marbach Archives and are printed in the article. Full bibliographical details can be found in the article: Ulrich von Bülow, Das Handwerk des Denkens- Zum Nachlass von Martin Heidegger. in: Auslegungen, ed. by Harald Seubert and Klaus Neugebauer. — Check the following pictures for more information. Thanks for reading!